What's it like waking up from a bilateral mastectomy?

How do YOU mark significant lived experiences?

Hello, friend!

Thank you for being here. I appreciate you. Even more so today.

You see, June holds many memories. Many good. Others not. June was the month of my bilateral mastectomy. Specifically, June 2, 2010. Yes, it’s been 15 years. A milestone you might say. A long time ago. Indeed. And yet…

I don’t mention this marker in time to anyone anymore (well, other than to you). Not even to Husband. No need. We remember every day each in our own way. The memory is mostly mine now. As it should be.

Which brings us to today’s essay. Since the memory is mostly mine now, I’ve been asking myself, should I even bother telling this story? Is there value to you, Dear Reader, in me sharing it?

Turns out the answer to both was yes. (Well, hopefully, you’ll agree about the latter.) These markers of significant points of my lived life matter. As do yours. When these markers roll around each year, how you choose to acknowledge them matters, too. If you choose not to talk about yours, don’t. If you want to talk about them, then do that. Of course, if your marker dates roll right on by and you don’t remember them at all, that’s fine, too.

The thing is, you get to decide.

At this point, sharing this piece isn’t for me. I share it because it might make a difference to someone who reads it—someone who’s facing this surgery today. Or will be next week, next month, or next year. I share it for them and for those who care about them, too.

If you are facing a mastectomy soon due to a breast cancer diagnosis or because of a prophylatic-surgery decision, I see you.

If you’ve had a mastectomy, or someone you care about has, I see you.

If you just want to learn about what it’s like waking up from a mastectomy, I thank you.

If you’ve faced a different, difficult surgery, or someone you care about has, I see you and want to know more about your experience.

After you’ve finished reading, let’s have a conversation. Let’s talk about a hard surgery (or other difficult medical experience) you’ve been through. Or one someone you care about has been through.

Let’s talk, too, about signifcant markers in our lives and how we choose to mark them, including not marking them at all.

Because as always, your hard matters, too.

If a paid subscription isn’t for you but you’d like to offer financial support, the PayPal Me option might suit you. It’s like leaving a tip. 🙂

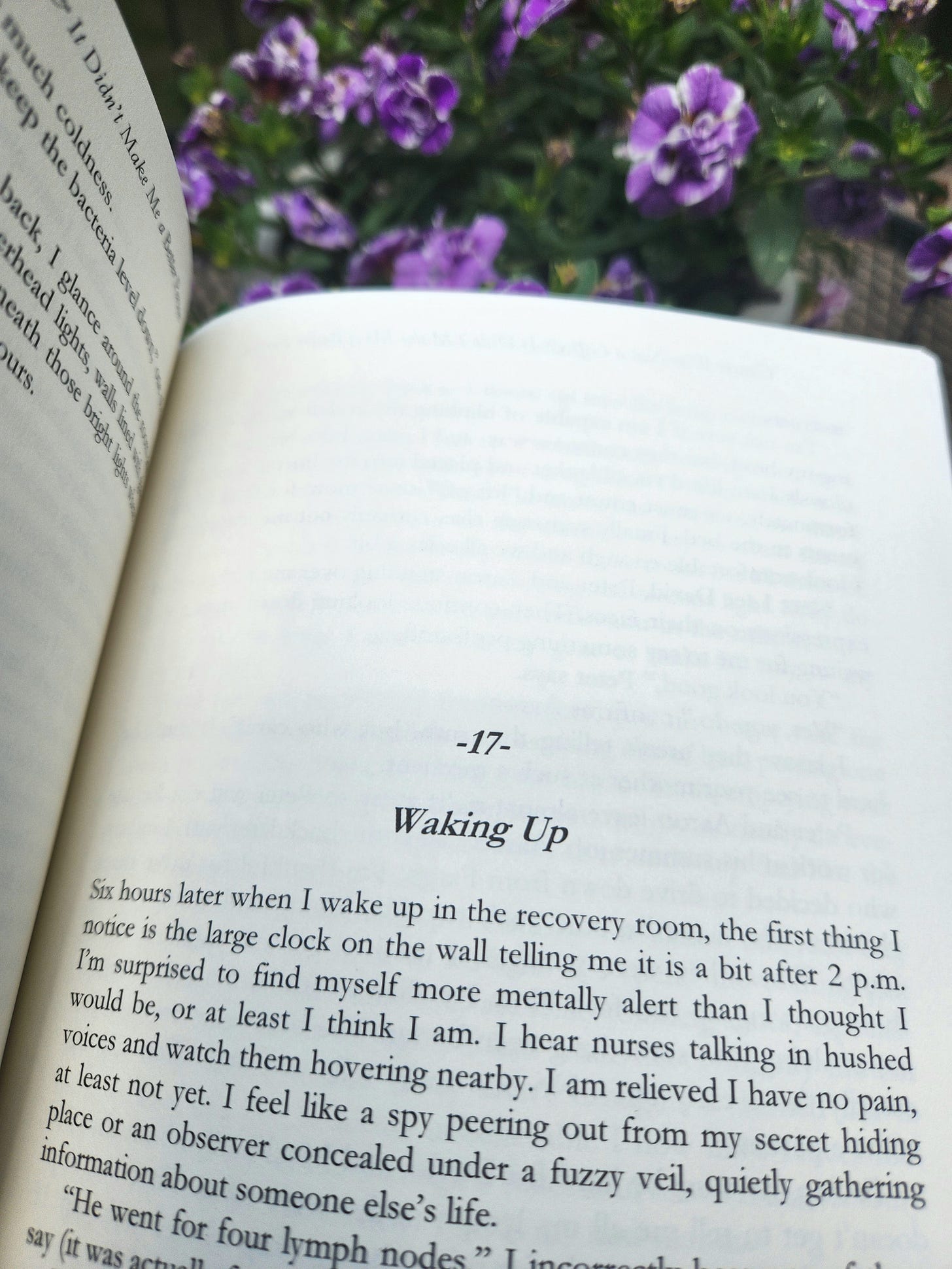

The following is a slightly edited excerpt from my memoir, Cancer Was Not a Gift & It Didn’t Make Me a Better Person: A memoir about cancer as I know it — Chapter 17. The names of family members have been removed for privacy.

Waking Up

When I wake up in the recovery room, the first thing I notice is the large clock on the wall telling me it’s a bit after 2 p.m. I’m surprised to find myself more mentally alert than I thought I would be, or at least I think I am. I hear nurses talking in hushed voices and watch them hovering nearby. I am relieved I have no pain, at least not yet.

I feel like a spy peering out from my secret hiding place or an observer concealed under a fuzzy veil, quietly gathering information about someone else’s life.

“He went for four lymph nodes,” I incorrectly hear one of them say (it was actually fourteen).

Immediately, I know they were not all clear. I can’t hear many other details, the voices sound too distant and muffled, but I listen intently as if I am decoding safely guarded, classified secrets.

As I continue to wake up, I am acutely aware I have been lying in the same position for well over six hours, and the idea of ever moving again feels like I might as well be trying to reach the moon. Eventually, after close to two more hours, I am pronounced ready by whoever decides such things, to be moved to my hospital room where Husband and my two sons wait for me. Daughter will come later tonight.

Still flat on my back, I am wheeled down numerous meandering hallways and finally end up in my assigned room. I brace myself when it’s time for them to transfer me to my hospital bed.

“We’ll count to three and then you try to lift your head,” someone instructs.

I’m not sure if I am capable of blinking my eyelids much less lifting my head, but they count anyway, and I guess I do, because miraculously I am lifted via a blanket and placed into the hospital bed. Unfortunately, we must count and “lift off” once more for final adjustments in the bed.

Finally someone, certainly not me, determines I look comfortable enough, and we all relax a bit.

Next, I see Husband and sons standing over me with worried expressions on their faces. They continue looking down at me, as if waiting for me to say something profound. I say nothing.

“You look good,” Son #1 says.

“Yes, you do,” echos Son #2.

I know they aren’t telling the truth, but who cares. It must be hard to see your mother at such a moment.

I feel badly they have become so familiar with cancer. They’re too young.

Facing me must be hard for Husband, and I feel badly about this, too. He doesn’t get to tell me all my lymph nodes were clear. That was supposed to be our secret code for things being okay when I woke up. If I heard the words “all clear,” we could celebrate. If I heard the words “all clear,” I would not need chemo.

I don’t get to hear them. We are both silent. Actually, I am too sick to think about much else anyway.

Coming out of anesthesia completely is like trying to free myself from quicksand. My mind feels clear and fairly alert, but my body seems stuck in slow motion, and I am unable to speed it up.

Every movement I want to make from the simple task of turning in bed, to pushing the buttons on my remote, to the more monumental feat of actually sitting up and getting out of bed, feels mechanical, slow and difficult. When I do finally manage to sit upright in order to make my way to the bathroom, I move slowly, like a woman decades older, and I am overcome with nausea.

“It’s okay,” Husband says.

He gently rubs my back as I throw up into the long, narrow, plastic blue bag.

Eventually, I make my way to the bathroom accompanied by a nurse and attached to my pain-relief-drug-filled IV bag, which is in turn attached to a cart on wheels. The nurse has instructed me that I am allowed to push a button on the machine every so often for an extra dose.

I push it.

There hardly seems to be room for all three of us in the tiny bathroom with its annoying fluorescent light. Why do they always buzz? I glance at my pale reflection in the mirror, but I don’t look for long. I don’t want my gaze to make its way to my chest, not yet.

When you are recovering from surgery, you no longer take for granted simple bodily functions such as rising out of bed, putting one foot in front of the other, brushing your hair or teeth, emptying your bladder or even breathing. Such simple motions you normally do every day with little notice or appreciation now suddenly feel like the most valuable skills in the world.

Son #2 returns this evening with Daughter. I’m relieved Son #1 is at work and doesn’t have to be here. We spend the evening just being together. I wonder what they are really thinking about, especially Daughter. I remember thoughts I had while observing Mother. They aren’t thoughts I wanted her to have, at least not yet.

It seems unbelievable I have cancer too.

However, I have just come through a successful bilateral mastectomy. My case will turn out differently.

This is my new mantra. I’m determined to believe it.

The four of us sit around doing little, but accomplishing much, simply by spending time together. Later after they all leave, I collapse into bed slowly; it is as much a mental collapse as a physical one.

June 2 is over. Thank God. My bilateral mastectomy is done.

I guess I’m now officially a survivor, or that’s what I’m told anyway. I have no idea what the hell this means. I do not feel like one.

Regardless, for whatever reason this situation has been assigned to me; there is no turning back.

I must look forward, and I will. Just not tonight.

Read more in my memoir, Cancer Was Not a Gift & It Didn’t Make Me a Better Person.

Read/download a sample HERE.

And now, let’s have that conversation. You’re invited to share whatever’s on your mind.

Have you (or has someone you know) had a mastectomy?

Have you been through a different, difficult surgery (or other medical experience) and recovery?

How do you mark significant markers in your lived life, or do you choose not to mark them at all?

If you feel my article has value, thank you for restacking it or sharing it with someone who might benefit from reading it. Clicking the ❤ at the beginning or end of this essay matters, too, as it signals to others you think it’s worth a read. (Thank you!)

One more thing, if this essay resonated, I encourage you to read a related article I wrote earlier: How to love your post-mastectomy body (when you really don’t). It’s one of my personal favorites since I began writing on Substack.

As always, I see you. I hear you, and I care about what you have to say.

Until next time…

Take care of yourself, be kind to someone, and be a light.

With much gratitude,

Nancy

Hi Nancy, I loved your memoir, and I thank you for reposting this excerpt. All your stories are important, and I strongly believe these stories are so crucial in helping you and others at least feel heard.

I'm so sorry you had to endure cancer and the horrific surgery that often comes with it. And I know it was so difficult for your family to endure this, as well. Surgery sucks. It just does. Cancer sucks, too.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer, my surgeon strongly recommended a lumpectomy, and I would get radiation and chemotherapy at the same time (the latter decided by my oncologist). I didn't want a single or double mastectomy, and my breast conservationist surgeon felt strongly that I should get a lumpectomy.

Later I would discover that this was a mistake.

My surgeon didn't get clean margins, so I had to have a re-excision, which totally deformed my right breast. And I remember the first time I had to drain fluid from the awful Jackson Pratt drains. I stayed in the bathroom and sobbed.

While my surgeon was competent, it didn't seem to bother him about my disfiguration, which is what in my mind had happened. And for the next five years after radiation and chemo, I would continue to get scares and live in hell. Finally after a doozy of a scare, I got a bilateral mastectomy with DIEP Flap reconstruction. My former breast surgeon told me not to do this. I fired him.

I reasoned that he may be knowledgeable about medicine, but he didn't know squat about my body.

Nancy, It’s comforting to be reminded that there’s no “right” way to hold a hard anniversary—and that sharing can be an act of care for others as much as for ourselves. Thank you for creating that space x